One of the best reasons to visit this year’s Whitney Biennial is Isaac Julien’s immersive multiscreen video installation, Once Again. . . (Statues Never Die), 2022, that also includes vitrines with Harlem Renaissance-era sculptures by Richmond Barthé, African sculptures, and contemporary works by Matthew Angelo Harrison. Julien interweaves historical footage and new images in the videos, which explore an imaginative discourse between the legendary Philadelphia-based collector Albert C. Barnes, and Harlem Renaissance philosopher Alain Locke concerning African art. In the process, Julien also merges images of the gay scene in London in the 1980s with an exploration of queer desire in Harlem in the 1920s. A museum exhibition within the exhibition, it is a stunning tour-de-force. Although the artist effectively creates a dreamlike atmosphere in the darkened space, I think it would have further enhanced the presentation if he boosted the illumination in areas where the Barthé pieces and other sculptures are displayed.

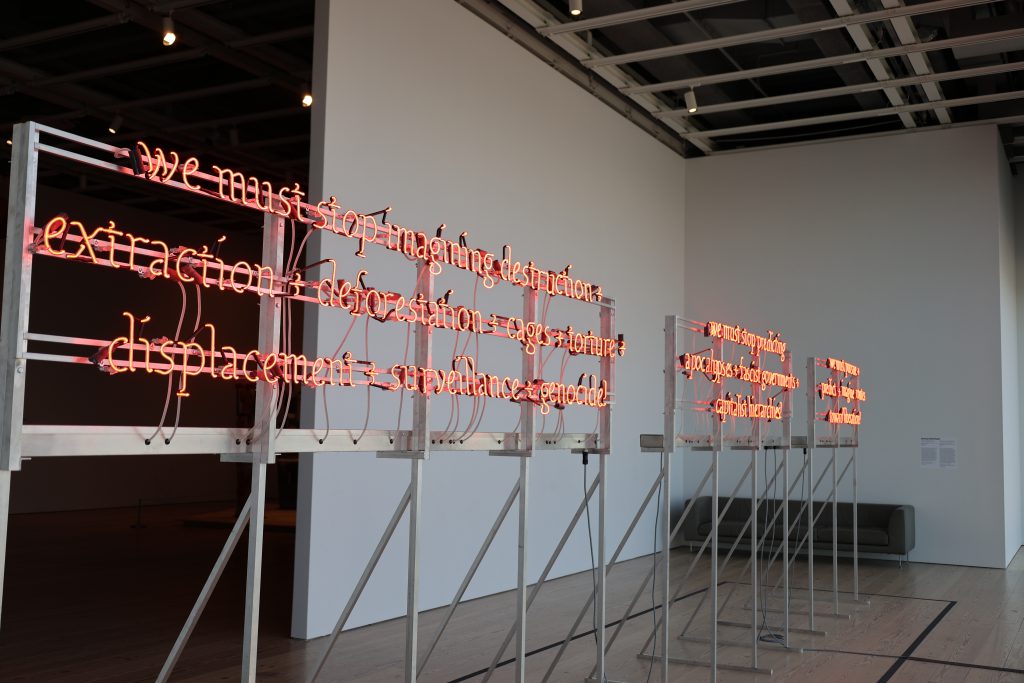

must imagine liberation, 2024, neon and steel, dimensions variable, collection of the artist.

Presumably, the preeminent U.S. showcase for artworld trends, the Whitney Biennial usually generates some kind of controversy or heated discourse about something. The current, 81st installment of the exhibition, with 71 participants, co-organized by Chrissie Iles and Meg Onli, and on view in New York through August 11, seems to go to great lengths to avoid any kind of dust-up. Full of light, color, and elegantly installed, there is nothing immediately confrontational here, certainly not on the level of Jordan Wolfson’s harrowing virtual reality piece Real Violence in the 2017 Biennial. That work, which immersed viewers in a brutal street mugging, certainly lived up to its title.

The closest thing to a stir here was caused by Demian DinéYazhi”s neon work, we must stop imaging apocalypse / genocide + we must imagine liberation, 2024, with rows of pink neon signage mounted on a metal scaffolding. Among slogans by various indigenous resistance movements, the words, “Free Palestine,” appear among the luminous texts. A bit Glenn Ligon-esque in its treatment of the neon text, this work, by an artist of the Navaho Nation, is one of the Biennial’s most striking. Any aggressiveness or even forcefulness that the work’s message may have had, though, is tempered by its placement. It faces out the museum’s glass walls in a narrow space; it is practically illegible from within the gallery. The work may have been far more potent if the glowing text faced the interior, or perhaps occupied a separate room.

steel cable, 69 1/2 × 32 × 24 in. (177 × 81 × 61 cm), Marieluise Hessel Collection, Hessel Museum of

Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY.

At first, I thought that the current Biennial’s title, Even Better Than the Real Thing, referred to the soulful 1968 R & B hit record by Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell, Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing; definitely not It’s the Real Thing Coca-Cola ad campaign. It turns out that the title was directly lifted from the 1991 U2 song, with lyrics like “We’re free to fly the crimson sky / The sun won’t melt our wings tonight.” That fanciful allusion to a romantic encounter seems far removed from the show’s purported theme–Artificial Intelligence and its growing threat to undermine any sense of reality. Julia Phillips’s striking sculptural pieces and paintings on paper here seem to correspond to the theme in the fusion of biology and technology that her works embrace. At once unnerving and captivating, the sculpture Nourisher (2022) shows a partially disembodied female figure with suspended ceramic breasts and head connecting to what appear to be intravenous feeding tubes.

Apparently, only one presentation, by the Berlin-based artist duo Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst, directly addresses A.I. technology and utilizes it in its theme and realization. The resultant series of large photos, xhairymutantx Embedding Studies, deserve to be highlighted for that reason alone. Each work features an image of a single figure in a puffy space suit, with long braids of orange hair, recalling a space-age Pippi Longstocking. Dismissed as overly slick and slightly corny by some critics, these works, I suspect, will likely be the most memorable for many Biennial visitors.

series), 1983; Oil, oil pastel, and glitter on canvas; 81 x 138 in. (205.7 x 350.5 cm)

Collection of the artist; courtesy Karen Jenkins Johnson

Despite its shortcomings, there is much to discover in this year’s Biennial. Although painting generally gets short shrift by the exhibition curators, some outstanding works are here, including the large-scale hyper-energetic quasi-abstractions by veteran California and Mexico-based painter Mary Lovelace O’Neal, associated with the Black Arts Movement in New York in the late 1960s. Once using predominately black pigment in her work, she eventually heightened her palette as well as the emotional intensity of the compositions in large-scale works such as Blue Whale a.k.a. #12, part of her Whales Fucking series (1979-early ’80s).

Zagreb-born New York artist Dora Budor makes an indelible impression here with sculptures, two-dimensional works and Lifelike, a disconcerting video presentation of street scenes shot with a shaking camera. It appears as footage from a documentary about an urban earthquake. Leaning nonchalantly against the wall, in front of a blocky benchlike sculpture, the video work adds an arresting destabilizing force to the Biennial’s otherwise tame proceedings.

Another outstanding work, by the Los Angeles-based artist P. Staff, imparts something of the trans experience they have lived by means of a room-size installation of diffused yellow light, and yellow vinyl walls. Visitors pass through the space whose ceiling is hung low with an electrified netting. It is an intimating and galvanizing environment, incongruously hostile and intriguing. Intensely thought-provoking in its theme of isolation, the work forcefully conveys the feeling of being an outsider.

Brooklyn-based artist Kiyan Williams confronts viewers on one of the museum terraces with an imposing sculptural rendition of the White House. Made of raw earth, the slanting building, like a dirty Leaning Tower of Pisa, the structure is surmounted by a flagpole with an upside-down American flag fluttering in the wind. An election year provocation, perhaps, the work does clearly speak to the current divisiveness in American politics and the precarious state of the country’s democratic institutions.

flooring, and video, color, sound; 67 min. Collection of the artist

Diane Severin Nguyen presents a glittery, fuchsia-seeped video installation In Her Time (Iris’s Version) that follows a fictional Chinese actress preparing for a film role in a movie about the 1933 Nanjing Massacre. Here is a mesmerizing sequence of glamour shots, bloody confrontation and hypnotic music that constitutes one of the most engaging and mesmerizing works in the Biennial.

Perhaps this Biennial’s strengths are best considered in formal terms, especially in the way socio-political themes may be expressed via the language of abstraction. Veteran artist and art-world feminist icon, Harmony Hammond, co-founder of the pioneering A.I.R. Gallery focused on women artists, and curator of the first-ever all-lesbian exhibition in 1978, offers here a group of large abstract paintings. At first, compositions such as Black Cross II (2020-21) appear to reference a range of key historical works of abstraction, from Kazimir Malevich to Frank Stella. Made from recycled fabrics, especially cloth associated with domesticity, such as tablecloths and quilts, they upend the traditional gender assignations of the material. In this way, Hammond’s works, with their imposing abstract shapes, can function metaphorically as formidable barricades against all forms of gender-biased microaggressions.

Diane Severin Nguyen, In Her Time (Iris’s Version), 2023–24

Isaac Julien, Once Again… (Statues Never Die), 2022